Why Europe's 'Chat Control' Proposal Will Cripple European Communication Industry While Failing to Protect Children

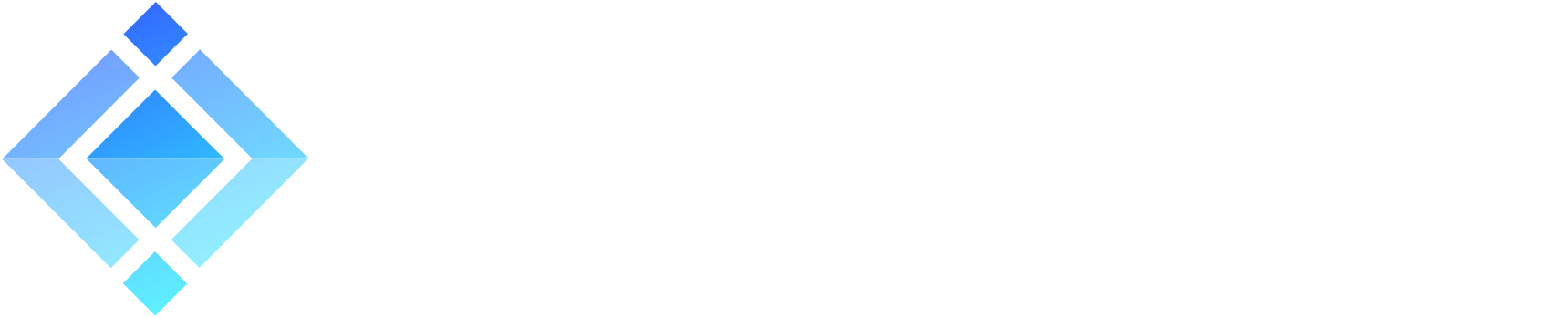

On October 14th, the European Concil will vote on a regulation that could effectively dismantle Europe's emerging decentralized messaging ecosystem, and shake the broader European communication industry while failing to protect the children it claims to defend. Driven by Denmark's fierce advocacy during its EU presidency, proposal 11596/25 – labeled 'Chat Control' by privacy advocates – finally faces a decisive moment after years of debate.

The proposal seems straightforward: require platforms to scan for child sexual abuse material. But the technical reality reveals a devastating contradiction: it demands the impossible from open, federated European alternatives while handing structural advantages to the very US tech giants Europe claims to want to regulate.

What the proposal actually requires

Proposal 11596/25 targets child sexual abuse material across a large range of services operating in the European Union: hosting services, interpersonal communications services, software application stores, internet access services, and online search engines. Under this regulation, these providers would be required to detect illegal content (images, URLs, text), report it to authorities, and remove it.

The scope goes far beyond what the European Parliament previously considered acceptable. In its balanced approach to child protection, Parliament explicitly rejected "widespread web scanning, blanket monitoring of private communications or the creation of backdoors in apps to weaken encryption." See: How the EU is fighting child abuse online.

This proposal abandons that restraint. It creates an obligation for service providers to scan all user traffic – encrypted or not – in search of illegal materials. More critically, it requires scanning private chat conversations before content is encrypted, not just publicly available content.

The risk of surveillance overreach

While child protection is undeniably crucial, the surveillance mechanisms described in this regulation create infrastructure that could threaten fundamental civil liberties. Once governments possess the technical capability to scan all private communications before encryption, the temptation to expand its use becomes overwhelming.

The concern isn't about protecting illegal content, it's about protecting democratic discourse. Private conversations could become subject to monitoring based on shifting political definitions of harmful speech. What begins as child protection infrastructure could evolve into a tool for suppressing political opposition or monitoring dissenting opinions in private communications.

The infrastructure created for child protection becomes the foundation that future governments — potentially less democratic ones — could leverage to monitor any communications they consider threatening to their power.

This is what privacy advocates primarily focus on, and their concerns are valid. However, as operators of messaging infrastructure, we face more immediate technical realities that make this regulation unworkable regardless of its civil liberties implications.

Why the technical requirements are impossible to implement

As operators of XMPP messaging infrastructure in sensitive industries, like for example the medical sector, we face the practical reality of what this regulation would require. The technical demands in Articles 7 and 10 reveal fundamental misunderstandings about how modern communication systems actually work.

The architectural reality: In-band vs. out-of-band content

Modern messaging platforms fundamentally separate data types. Messages and protocol data transfer "in-band" through the messaging protocol, while binary content like images and documents transfers "out-of-band" because files are too large for messaging channels.

This creates an immediate problem for the regulation's scanning requirements. When doctors share diagnostic images through our XMPP platform, the system works like this:

- Clients negotiate the exchange via XMPP (metadata visible to server)

- The medical file transfers peer-to-peer or via HTTPS upload with a unique, secure link

- The messaging server never sees the actual content – only the negotiation

The regulation can only scan in-band messaging content and metadata, not the out-of-band transfers where sensitive material could actually reside. It will break confidentiality of legitimate medical discussions without accessing the data it claims to monitor.

The open protocols impossibility

Article 10.1's requirement to scan "prior to transmission" in end-to-end encrypted services assumes complete client control -- something impossible with open protocols like XMPP.

The regulation demands that service providers guarantee scanning occurs before encryption on every client. But XMPP is a standardized, open protocol where anyone can develop compatible clients. On an average XMPP server, more than 30 different clients coexist. How can we guarantee that each client respects scanning obligations when we cannot control their code?

The problem deepens with federation. XMPP servers interconnect, allowing users on different servers to exchange messages. When a message arrives from another server, it's already been end-to-end encrypted by a client we have no control over. There's no technical mechanism for the receiving server operator to enforce scanning requirements on clients that are not directly connected on its platform.

This creates an absurd regulatory requirement: we would need to either abandon open standards entirely or somehow police every piece of software that implements XMPP, including modified open-source clients that users could easily deploy to bypass scanning.

The circumvention reality

Real criminals can easily bypass these measures through three complementary approaches that the regulation fails to address:

Distributed architecture: Store content on external servers and share only URLs through chat, exactly what legitimate services like our XMPP platform already do naturally for file transfers.

External encryption: Encrypt content with PGP, GnuPG, or OpenSSL before uploading it anywhere, making scanning meaningless regardless of the platform's capabilities.

Modified clients: Use altered XMPP or Matrix clients that automatically implement these behaviors, exploiting the same open-source flexibility that makes compliance impossible.

The result is predictable: the regulation will only catch criminals amateur enough to send illegal content directly as unencrypted attachments through unmodified clients. Meanwhile, it subjects all legitimate communications of European citizens to mass surveillance.

This isn't theoretical speculation. These methods are already standard practice across European messaging infrastructure, used by both legitimate services and bad actors alike.

The programmed death of European alternatives

This regulation creates a structural disadvantage for European communication services trying to build alternatives to US tech giants.

Complexity favors incumbents

Annex XIV reveals a scoring system of Kafkaesque complexity, requiring considerable resources for compliance. This complexity structurally favors large platforms, usually Americans, that can:

- Deploy massive financial resources to adapt their systems

- Control their closed ecosystems completely

- Distribute compliance costs across billions of users

The decentralized ecosystem under threat

Meanwhile, Europe's emerging decentralized alternatives face impossible technical requirements. There are currently tens of thousands of independent XMPP servers, federated Matrix deployments, and GDPR-compliant solutions that represent Europe's best chance for digital messaging independence. Can they comply with obligations designed around centralized architectures?

We operate several messaging servers on behalf of customers. Under this regulation, we face a stark choice: shut down services we cannot control completely, from clients to servers, or force our European clients to migrate for example to Microsoft Teams to avoid regulatory complications.

Conclusion

This technical analysis reveals a regulation that fails on multiple levels. It demands technical impossibilities from European service providers while offering trivial workarounds for actual criminals. It structurally advantages US tech giants over European alternatives at precisely the moment Europe seeks digital independence.

For communication service operators, this regulation creates an impossible choice: abandon open protocols and federated architectures that represent Europe's best path to messaging independence, or face legal risks with high mitigation costs even in lawful, legitimate use cases.

The October 14th vote represents more than a policy choice about child protection. It's a decision about whether Europe will cripple its own communication infrastructure in pursuit of surveillance capabilities that won't work as promised.

The current compromise proposal has been shared here: Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down rules to prevent and combat child sexual abuse - Presidency compromise texts. This seems is the most up to date version of the text I could find. Read the text and make your own assessment of whether Europe can afford to implement technical requirements that its own industry cannot comply with.